Endangered Animal

Axolotl

-

-

The axolotl is endemic to Mexico City. The only wild ones left survive in the canals of Lake Xochimilco. Current estimates suggest fewer than 100 adults remain in the wild.

I visited Lake Xochimilco two years ago. They had these small “museums” with axolotls kept in shallow pools, about two by two meters, with almost no water. The animals looked uncomfortable, nervous. People walked in and touched them with dirty hands. I had expected to feel some hope by visiting, but instead it was depressing—a brutal showcase of how disconnected they are from their real habitat.

Water quality is the most immediate threat. Farms in the region dump partially treated wastewater and agricultural runoff into the canals. That water is full of pesticides and chemicals that destroy embryos and larvae. Even those that survive often show deformities or die young.

Another major problem is invasive species. In the 1960s and 70s, carp and tilapia were intentionally introduced for fishing and commercial purposes. Large fish eat axolotl eggs and juveniles, while smaller fish compete with them for food, hiding places, and breeding areas.

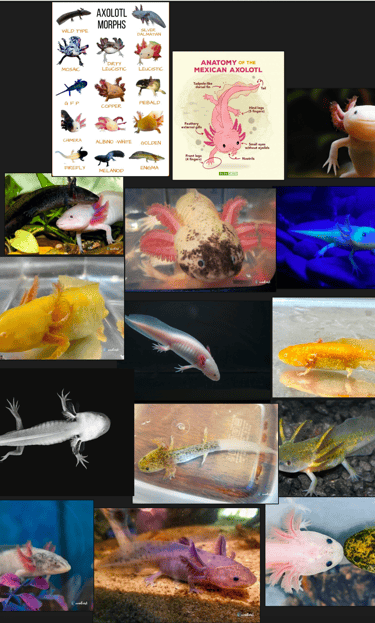

Axolotls are curious creatures. They enjoy exploring their environment slowly, usually at night, and they have a solitary and secretive nature. They prefer to walk along the bottom of their habitat, which earned them the nickname “walking fish.” They breathe through their frilled external gills, but also possess rudimentary lungs. When oxygen levels in the water are low, they rise to the surface to gulp air. Their regenerative powers are remarkable—they can regrow limbs, and even parts of their eyes and brains.

Despite their uniqueness, and even though they’ve become a symbol of Mexican identity, and have appeared on our $50 bill in recent years, that recognition hasn’t translated into real protection. The axolotl is hanging by a thread in its only natural home. Imagine going from a vast wetland across the Valley of Mexico to a few polluted canals, invaded by predators. The humans who live there—who should be the protectors of this habitat—have instead destroyed it. We, the Mexican government and the people of Mexico City, have failed as guardians.

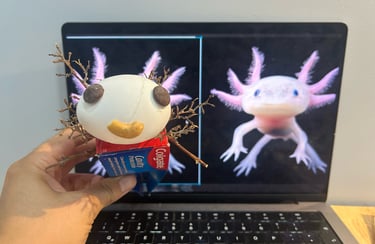

My first step was reviewing the garbage I had collected over the last few days. I laid everything out—cartons, plastic, egg shells, grape branches, an old toothpaste box. Then I gathered reference images of the axolotl. I focused on the body proportions and the traits that make them unique. The axolotl has a very recognizable look: a wide face, an oval-shaped head, and in most pictures it seems to carry a smile, a calm and almost happy expression.

With this in mind, I started thinking about the basic forms. I noticed that if I closed an eggshell back together, it gave me the rounded shape of the head. Then I realized I could use the grape branches for the gills—the thin, branching structure was perfect for this.

The next step was adding a body. I needed a piece that wouldn’t overpower the head, so I cut down a toothpaste box and used that as the torso. I attached some of the thicker grape branches to make the arms, making sure the proportions matched what I was seeing in the reference images.

Little by little, the axolotl started to take shape, turning into something that felt alive—or at least a small reminder of life.My first step was reviewing the garbage I had collected over the last few days. I laid everything out—cartons, plastic, egg shells, grape branches, an old toothpaste box. Then I gathered reference images of the axolotl. I focused on the body proportions and the traits that make them unique. The axolotl has a very recognizable look: a wide face, an oval-shaped head, and in most pictures it seems to carry a smile, a calm and almost happy expression.